|

In this five-part series, CompetitionPlus.com will explore ten races that were really great at one time, and some were famous, while others were obscure. The bottom line is they were fun and epitomized the spirit of drag racing.

We will undoubtedly miss a few, but save your judgment until the series ends. Special thanks to Bret Kepner, Dave Wallace, Steve Earwood, Mark Hendon and others who helped ensure this series came to fruition with their knowledge of the sport and willingness to contribute.

THE ORIGINAL IHRA WORLD NATIONALS, NORWALK, OHIO

The IHRA World Nationals grew into one of the most successful sanctioned drag races because of a combination that worked. The sanctioning body needed more races to compete in an ever-expanding drag racing world and a relentless track owner in his pursuit of excellence despite the odds stacked against him.

The IHRA World Nationals grew into one of the most successful sanctioned drag races because of a combination that worked. The sanctioning body needed more races to compete in an ever-expanding drag racing world and a relentless track owner in his pursuit of excellence despite the odds stacked against him.

In 1981, Bill Bader and Norwalk Raceway Park got the chance to run with the big dogs and took advantage of every opportunity.

What race fans see today is a palatial race facility immaculately groomed in Summit Motorsports Park and routinely delivers one of the best drag racing bangs for the buck. It is a drag strip with which a race fan and a racer can easily fall in love. Sometimes, it has everything to do with the creature comforts and customer service, and that’s where the IHRA World Nationals made a name for itself.

Bill Bader had a dream of having a national event at his facility, located outside of Cleveland, Ohio, and when he approached the NHRA about getting one, they were firm in their decline. He then approached the less stringent IHRA

The significantly more compromising International Hot Rod Association considered the proposal but reluctantly agreed to the stipulation that certain improvements be made. By today’s standards, those improvements would have been the equivalent of bringing in bulldozers to level everything and start over from scratch.

The man in question was Bill Bader, and the track is the now highly regarded Summit Raceway Park. In the beginning, however, Bader didn’t know what he was getting himself into.

Ted Jones, then the vice president of the IHRA, arrived at the track early in the week before the event to watch the whirlwind of activity created as Bader struggled to finish the work and comply with several construction codes.

The late Bill Bader Sr., in an interview with CompetitionPlus.com, remembered the days before the event.

“He saw it was under construction,” Bader said regarding Jones’ arrival at the track. “We weren’t scheduled to open the gates until Friday morning, but we had lots and lots of work to do. There was no guardrail in place for the first six hundred feet. There was no chain link fence, and the grandstands were just being finished.

“Ted said to me, ‘Bill, how’s it going? The race is this week, you know.’ I told him the race is Friday, and this is Monday, so get the hell out of my way so I can get it finished. I think Ted was very nervous at that point,” Bader said in a classic bit of understatement.

Bader and his gang even had to wash the track down because the racing surface had become a staging area for the newly purchased grandstands. On Thursday evening, the construction was still underway, which prompted Jones to remind Bader that they needed the track on Friday.

“I assured him it would be ready by morning,” Bader said.

The biggest reason construction went to the wire was the weather. “With our winters, the building season was very limited,” Bader said. We had to do the most work we could in a very limited amount of time.

The original grandstands at NRP were purchased from a local baseball field and had a capacity of just over 800. In advance of his first national event, Bader replaced those with bleachers capable of seating 9,000 paying customers. The new stands were bought from York U.S. 30, moved in before the event, and assembled in the snow.

The original grandstands at NRP were purchased from a local baseball field and had a capacity of just over 800. In advance of his first national event, Bader replaced those with bleachers capable of seating 9,000 paying customers. The new stands were bought from York U.S. 30, moved in before the event, and assembled in the snow.

“We didn’t even have a scoreboard or a return road when we were awarded the event,” Bader said. “The grandstands weren’t even put up. The challenge of getting that done between the weather, time, and staffing made it difficult. The preparation went down to the 11th hour.

“I asked myself, ‘Why did that happen?’

“It’s the age-old tradition of trying to get ten pounds of work done in eight pounds of time.

Jones recalled his first Norwalk Experience during the days leading up to the inaugural Norwalk event.

“The place was horrible and barely acceptable,” Jones, now a retired motorsports television producer, recalled. “We had to get Bill to put in the contract many things that had to be done before we ran the event. The thing with Bill is that he just kept improving. After a while, we didn’t have to require things – he just got it done.”

By all accounts, this was a minimum-standard event. Even the timing system was not up to “code.”

“Bill didn’t use the Chrondek timing system that had the 12-volt light sources,” Jones said. “Those were break-away bulbs so as not to damage the cars. He had 120-watt, 150-volt spotlights that you would put on the outside of the house. He fastened his light source to a concrete block. Obviously, that would do a fair amount of damage to the cars. We had to let him know that he couldn’t use that.”

Jones said Bader complied with the IHRA’s request to switch to the current IHRA photocell system. One thing that impressed Jones was the way Bader became motivated, and the two entities learned equally from one another.

“The thing that motivated him the most was seeing these events’ potential,” Jones said. “We learned a lot from him and vice versa. It opened a lot of doors for him as far as future large events were concerned.”

That first event, the 1981 Winston World Nationals, was an abysmal failure financially for Bader and the IHRA. According to Bader, the event cost $110,000 to produce and they lost $55,000.

That first event, the 1981 Winston World Nationals, was an abysmal failure financially for Bader and the IHRA. According to Bader, the event cost $110,000 to produce and they lost $55,000.

“Raymond Beadle walked up to me and asked me if I wanted to flip for $50,000,” Bader said. “He asked me how much I stood to lose. He wanted to flip me for it. God bless him. He was being funny, and I wasn’t much in a funny mood.”

That first event only attracted six nitro and two alcohol funny cars. Then, IHRA President Larry Carrier approached Bader with an idea that could improve or further damage the bottom line. Bader didn’t know that Carrier was baiting him to test his resolve.

“He asked me if I wanted to let the alcohol cars run,” Bader said. “He presented the option of letting them run, but it would have cost us first-round money for both on an event that was already losing money. He asked me what I wanted to do.

“I told him that if we wanted to grow this race, we had to give the fans an eight-car field, and those were the best eight cars we had. I told him the only problem was that I didn’t know if I had the money to cover my end of the loss. Carrier then spoke up and let me know he would loan me the money.

“He just wanted to see what I was thinking,” Bader said. “That was a good lesson and a good moment between the two of us.”

But Bader was right in so many ways: The fans deserved a good show. Though it was a financial disaster, the entertainment value of the event started an upward trajectory that would make it one of the most fan-friendly events in drag racing.

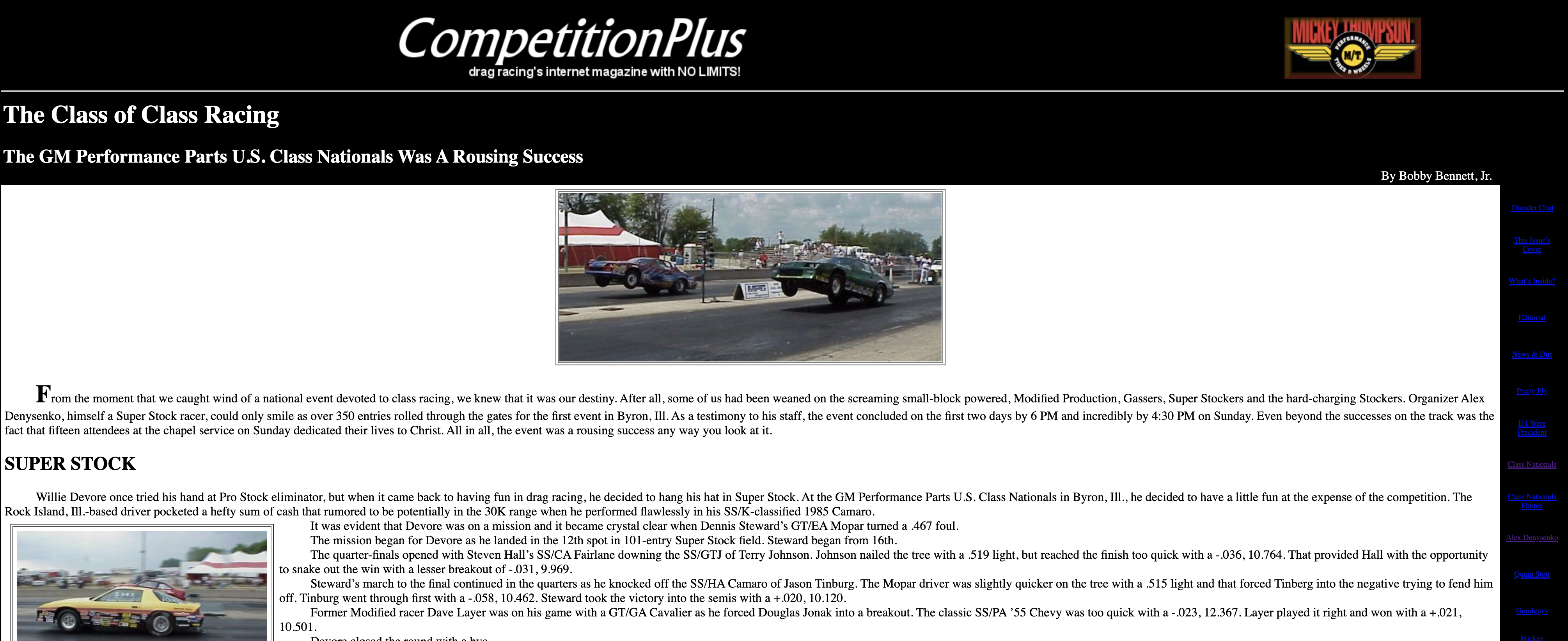

THE U.S. CLASS NATIONALS, BYRON ILLINOIS

If there was ever a Woodstock for sportsman drag racing, the U.S. Class Nationals in Byron, Illinois, filled the role perfectly. And maybe it wasn’t so much of a Woodstock as it was racers trying to prove a point.

If there was ever a Woodstock for sportsman drag racing, the U.S. Class Nationals in Byron, Illinois, filled the role perfectly. And maybe it wasn’t so much of a Woodstock as it was racers trying to prove a point.

Alex Denysenko passed away in 2016, but his words live on in the pages of CompetitionPlus.com, which attended and covered the inaugural U.S. Class Nationals.

Denysenko shared with CompetitionPlus.com in a 2001 interview the impetus for creating the event.

“I was in Norwalk last year and I went four rounds of competition, and I left the track with $100 in prize money,” said Denysenko, who raced a Super Stock/L Automatic Mustang. “I went to Indy and went five rounds, got down to eight cars, and left with $500. I said to myself, ‘Oh boy.”

“I knew at that moment that someone needed to do something for the Stock and Super Stock racers. We spend a week at the races, especially at those two. We are relegated to the back of the bus in everything, including parking, our run schedule, and when we can run. There’s never a real schedule, and we never run for any sizeable purse, yet we pay the most entry fee for any class contested. We get the least compensation for the work and effort we put into our cars.

“Drag racing, from a spectator standpoint, was based on the Stock and Super Stock cars. These are cars that you could buy and go out on the street and race. Then you could go out to the track and see what it would run. You came to the track on Sunday to see who won and then you could go to the showroom and buy it on Monday. That’s what I always loved and I followed it as a kid. I fell in love with it, and it was the only kind of racing that I wanted to do.

“I have watched it deteriorate, but that wasn’t because of the quality of the cars. It was the sanctioning bodies that continued to push us away because we require the greatest amount of work. We have specific rules and specific parts that have to be on our cars. There’s no gray areas and everything is specific. It requires talented tech people and it requires a lot of paperwork. It’s more than the sanctioning bodies want to put up with and there’s not enough compensation for them to deal with it. I just felt that someone needed to bring all of the Stock and Super Stock cars together and put on a decent event and pay some decent money and prove to everyone that fans will come to see us.”

“I have watched it deteriorate, but that wasn’t because of the quality of the cars. It was the sanctioning bodies that continued to push us away because we require the greatest amount of work. We have specific rules and specific parts that have to be on our cars. There’s no gray areas and everything is specific. It requires talented tech people and it requires a lot of paperwork. It’s more than the sanctioning bodies want to put up with and there’s not enough compensation for them to deal with it. I just felt that someone needed to bring all of the Stock and Super Stock cars together and put on a decent event and pay some decent money and prove to everyone that fans will come to see us.”

Denysenko was right in that it drew 1,200 spectators, a number higher than most divisional events at the time, and over 300 entries. He went to the 2000 PRI show with the idea of a 5000-to-win, 2500 runner-up program with the payoffs substantially larger all the way down. There were 120 sponsors that signed on to support the event, which had full-bodied cars only with Top Stock, Super Stock, and Stock Eliminators.

“For the first time, we brought both IHRA and NHRA cars together on the planet in a common event,” Denysenko explained. This is the first time that IHRA and NHRA cars have run together simultaneously under mildly modified rules just to accommodate one another.”

In the end, the racers did what they set out to do.

Jeff Lee, now an advertising agency executive, was the webmaster for the IHRA and a kid who grew up in class racing. He was part of the group assembled by Denysenko to bring the vision to reality.

Denysenko proposed, and on the Stock/Super Stock forum, the idea took on a life of its own.

“This was long before classracer.com, and there was a lot of discussion about what if we had just a national event for Stock and Super Stock and all those class cars,” said Lee, a college student at the time.

Lee joined a consortium of class fans such as Anotol Denysenko, “Nitro” Joe Jackson, and Fred “The Sarge” Elsass.

Byron Dragway was a track with roots in sportsman racing from its Bracket Nationals days of the 1970s and 80s. It was also a facility with whom Denysenko had a great repertoire.

Byron Dragway was a track with roots in sportsman racing from its Bracket Nationals days of the 1970s and 80s. It was also a facility with whom Denysenko had a great repertoire.

The format produced a great weekend of racing and established the value in National Open events for the major sanctioning bodies.

“I think it inspired these smaller sportsman groups to come together and promote their own events,” Lee said. It felt really special, and everybody was super excited to do it, to have their own event. So, I think that led a little bit more credibility to it, and I think we really promoted it well via the Internet and to all the regional racers. There were guys who came from Canada, California, and all over the country to Byron, Illinois, for this one event.

“We tried to pick an event date that had minimal conflicts with any NHRA or IHRA national events, and I believe IHRA and NHRA supported it to a limited extent. We had some IHRA tech people there, and IHRA covered it.

In the end, Denysenko and his team proved a point, and they encountered some help and roadblocks along the way.

In the Competitionplus.com July 2001 interview, Denysenko laid out the landscape.

“Up until very recently, it was nothing but very negative,” Denysenko said. “Bill Bader, I ran the concept by him at the PRI show, he rubbed his chin, gave me a big Bill Bader hug, and told me that it was an incredible concept. He said that the NHRA and IHRA have not been able to do that for 30 years. Bader told me that anything I needed, he was behind me 100 percent. He offered whatever help he could financially, technically, and personnel, and within reason, he’d do it.

“The NHRA and I will not give any details; we did nothing but throw roadblocks in my way. They issued a mandate that IHRA cars had to have an NHRA certification even though they are certified by IHRA and are on an NHRA track. Mike Baker admitted that he accepts NHRA certifications at the IHRA racers. What’s the problem? The two of them go through the same SFI tech school, yet it was another roadblock.

“The IHRA went out of their way to promote and advertise the race on Drag Review and on the Internet. I couldn’t get anyone to return a call or an email at the NHRA. Yet, they talked about the event all the time. Until the event began to gain steam, and Len Imbrogno got behind it and then went to the NHRA and told them that they couldn’t ignore this thing because it was a lot bigger than they were giving it credit for.

“They became aware of it and they gave us a blurb here and a blurb there in National DRAGSTER. Our Division 3 director began to give us some help. For the first six months the NHRA did a lot to hinder us and nothing to help us. They advised people not to come work for us. We had key NHRA tech people that had originally agreed to help us and work in tech and were told by their bosses that it would not be in their best interests if they came to work this ‘outlaw’ event as it was called.

“The two NHRA people that I got to help us actually put their jobs in jeopardy by coming here. They love Stock and Super Stock; they are our friends, and that’s why they came and did it. The IHRA people are on the payroll. Bill Bader sent them here.”

THE COMPLETE LIST

1 – THE NHRA SUMMERNATIONALS, Englishtown, NJ

It was hotter than all get-out at the Englishtown NHRA Summernationals; the humidity was so thick it was like sludge, and the race fans sometimes seemed drunk and belligerent. But, it was some of the best drag racing memories to behold.

It was hotter than all get-out at the Englishtown NHRA Summernationals; the humidity was so thick it was like sludge, and the race fans sometimes seemed drunk and belligerent. But, it was some of the best drag racing memories to behold.

During downtime, there would be chants of “the other side sucks” and maybe even a mooning or five. When NHRA expanded its schedule to 24 races, there were times when one could close their eyes, listen to the sounds, and not immediately know where they were. In Englishtown, you knew exactly where you were.

“Every track has a personality, and Englishtown had a very strong one, no question about it,” noted drag racing historian Bret Kepner added.

The Summernationals was staged at other NHRA tracks, and Raceway Park ran other events on the NHRA tour. But this event, when partnered with the Napp Family’s neighborhood facility, produced some of the best entertainment in drag racing.

The Summernationals entered the tour in 1970 as part of the NHRA’s Super Season initiative and ran at York’s U.S. 30 Dragway in Pennsylvania for just one season.

“York was a good race, but York also couldn’t handle very much of a crowd,” Kepner said. “Maybe the place seated maybe six or 7,000, which was one of the biggest at the time. No question about it.”

Raceway Park in Englishtown, which had run the 1968 NHRA Springnationals, returned to the tour in 1971; after spending two seasons improving, the facility remained on tour until 1992, when the track’s event was moved to May and renamed a sponsored Nationals.

The Summernationals triumphantly returned in 2013 until the last NHRA race was run there in 2017.

The Summernationals triumphantly returned in 2013 until the last NHRA race was run there in 2017.

“When we thought of the Summernationals, we didn’t think of the event name; we thought of Englishtown,” said Top Fuel racer Antron Brown, who grew up at the track. “That’s where it all went down.”

“For me, Englishtown Raceway Park was always the Summernationals,” NHRA Funny Car champion Ron Capps said. “The cool part to me is what happened in the history there. Looking back on some of the coolest experiences, as a kid in California, happened there.”

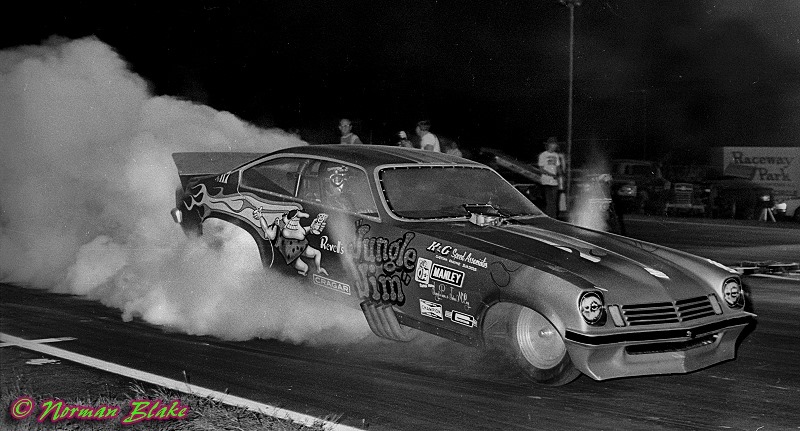

Indeed, there was the first husband and wife championship final between Judy and Dave Boertman. There was “Jungle Jim” Liberman’s first national event win, Frank Iaconio beating the seemingly unbeatable Glidden in the 1979 race, and the event favorites Don “The Snake” Prudhomme and Shirley “Cha Cha” Muldowney pulling down event wins. John Force reached his second career final round at the 1979 event.

Of course, there were the commercials with the fast-forward sound of Raceway Park!

“Englishtown was a state of mind,” wrote drag racing fan David Hapgood for DragList.com. “To understand this better, you’d have to rewind the clock about forty years. What was it like to visit Englishtown back in the day? For starters, unless you lived near the track, it involved a trip into the NYC metropolitan area, the most densely populated region in North America. Inevitably, this meant a nice drive on the New Jersey Turnpike, a writhing mass of multi-laned asphalt that snaked through the center of the state.

“Englishtown was a state of mind,” wrote drag racing fan David Hapgood for DragList.com. “To understand this better, you’d have to rewind the clock about forty years. What was it like to visit Englishtown back in the day? For starters, unless you lived near the track, it involved a trip into the NYC metropolitan area, the most densely populated region in North America. Inevitably, this meant a nice drive on the New Jersey Turnpike, a writhing mass of multi-laned asphalt that snaked through the center of the state.

“If you were coming from the north, you were driving in NYC traffic; from the south, you were in Philadelphia traffic. And if you were paying close attention, you might spot the Berserko Bob sticker that some race fan had stuck on one of the toll booths. In any case, the turnpike was the portal that transported you into what was then the semi-rural world of central New Jersey. But your destination that day wasn’t Old Bridge Township Raceway Park, as nobody called it that. It was known simply as Englishtown or E-Town, ground zero for drag racing on the eastern seaboard.”

The Englishtown facility was often used in feature films, most notably Heart Like A Wheel and the lesser-known Wheels of Fire, and this was no double credited to the facility’s Summernationals legend.

On January 16, 2018, the facility officially notified the NHRA it would no longer be hosting any drag racing events, effectively ending the run of the iconic event in New Jersey just shy of its 49th annual Summernationals.

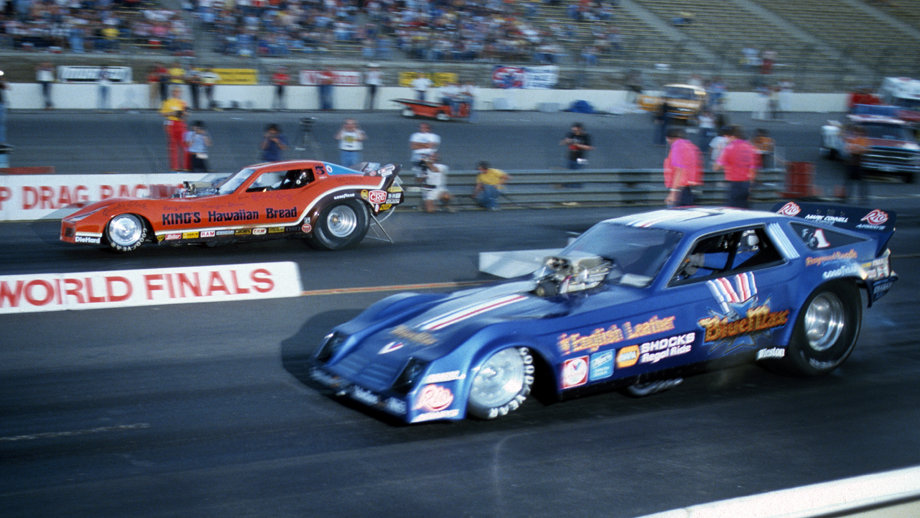

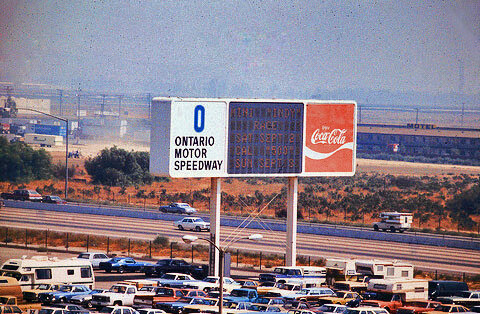

2. THE NHRA SUPERNATIONALS/WORLD FINALS – Ontario, Ca.

Maybe this isn’t so much of a race we miss as it is a longing to have another event at the long-gone Ontario Motor Speedway. If zMAX Dragway, built on the hallowed grounds of Charlotte Motor Speedway, is considered The Bellagio, the track in Ontario, Ca., could be considered The Venetian.

Maybe this isn’t so much of a race we miss as it is a longing to have another event at the long-gone Ontario Motor Speedway. If zMAX Dragway, built on the hallowed grounds of Charlotte Motor Speedway, is considered The Bellagio, the track in Ontario, Ca., could be considered The Venetian.

The Ontario Motor Speedway first entered the NHRA sphere as part of the 1970 Super Season with a non-points-earning event sponsored by Hot Wheels, the famous Mattel brand. The groundbreaking 1970 Supernationals was broadcast live on national television. The television couldn’t do justice to all the other “stuff” the Supernationals offered courtesy of its host, the $25.5 million Ontario Motor Speedway.

The professional competitors worked in their own individual garages. Because of the massive size of the facility, there were Disneyland-type shuttle buses, taking spectators on motorized strips through the pits. There was also a restaurant overlooking the strip, where one could dine fashionably while watching the races. Oh yeah, and there was a drag race going on.

The Supernationals became the place where drag racers came to establish records and fans came to watch them, all on a strip of asphalt also used as a pit road lane for the oval track. This didn’t come until the 1972 event when the NHRA staged the event as an all-professional show. Mike Snively powered “Diamond Jim” Annin’s dragster to the first-ever five-second elapsed time, and “Big Jim” Dunn drove a rear-engined Funny Car to its only win. While Snively made history, Don Moody left with a record 5.91 elapsed time. Bill Jenkins won Pro Stock, beating the newcomer Bob Glidden.

The Supernationals became the place where drag racers came to establish records and fans came to watch them, all on a strip of asphalt also used as a pit road lane for the oval track. This didn’t come until the 1972 event when the NHRA staged the event as an all-professional show. Mike Snively powered “Diamond Jim” Annin’s dragster to the first-ever five-second elapsed time, and “Big Jim” Dunn drove a rear-engined Funny Car to its only win. While Snively made history, Don Moody left with a record 5.91 elapsed time. Bill Jenkins won Pro Stock, beating the newcomer Bob Glidden.

The NHRA retained the all-pro show in 1973, resulting in 60, yes 60, Top Fuel entries and 40 Funny Cars. The event resulted in the quickest and fastest runs in both fuel categories. A year after Top Fuel broke into the five-second zone, Garlits ran a 5.81.

The facility was more than breathtaking, as drag racing historian Kepner noted.

“I was lucky enough to have gone, and there never has, nor never will be, a drag strip like that,” Kepner said. “It was just surreal. There aren’t enough adjectives to accurately describe that place. It was just, I mean, the whole story of Ontario; it was surreal. That place should have never been built. It was an auto racing facility times a million. When that place opened its doors, there was no way that it wouldn’t go bankrupt in a year. And that’s exactly what happened. It went bankrupt several times.”

The Supernationals morphed into the World Finals championship event in 1974, and those who attended understood, like many big-money tickets in drag racing, were unsustainable financially. Even the most seasoned drag racing entities like Kepner still get giddy when talking about the place.

“The facility was… mind-boggling doesn’t even cover what that place was like,” Kepner explained. “That tower at the finish line of the drag strip, the media tower above the grandstands, was so high in the air it was like watching ants go down the drag strip. It was just monstrous. I have no idea what the actual altitude of the media room was, but it was astounding. You could go outside the press room on a huge balcony around the entire facility, lean on the balcony’s edge, and watch the races. It was just incredible.”

The racers looked at the place with the same feeling even though they did a burnout facing the grandstands in the first couple of events and turned left to go to the starting line.

The OMS facility was built with a 2.5-mile oval and, at the time, a groundbreaking part of racing architecture – a tunnel. When you came out on the other side of the tunnel, there were multiple large metal doors with a sign proclaiming, “Behind these doors is the most powerful public address system ever built by man.”

The NHRA raced there once a year, and interestingly, only three months away from the Pomona season-opener in the same market.

“Los Angeles was a big enough market to handle it,” Kepner said. “Ontario drew good crowds for a drag race. It just was a drop in the bucket to what it needed to stay open because of the size of the facility. And the IndyCar and NASCAR races never came close to making enough money to keep that place open. That was what the real draw was.”

Ironically, the largest crowd OMS ever drew was a California Jam rock concert, in which many tracks had those mid-70s rock festivals that bailed them out.

Interestingly, the Supernationals was always a promotional success, considering NHRA never began the event promotions until after the World Finals.

OMS closed after the 1980 season, just a decade after it produced one of the most extraordinary drag race events ever.

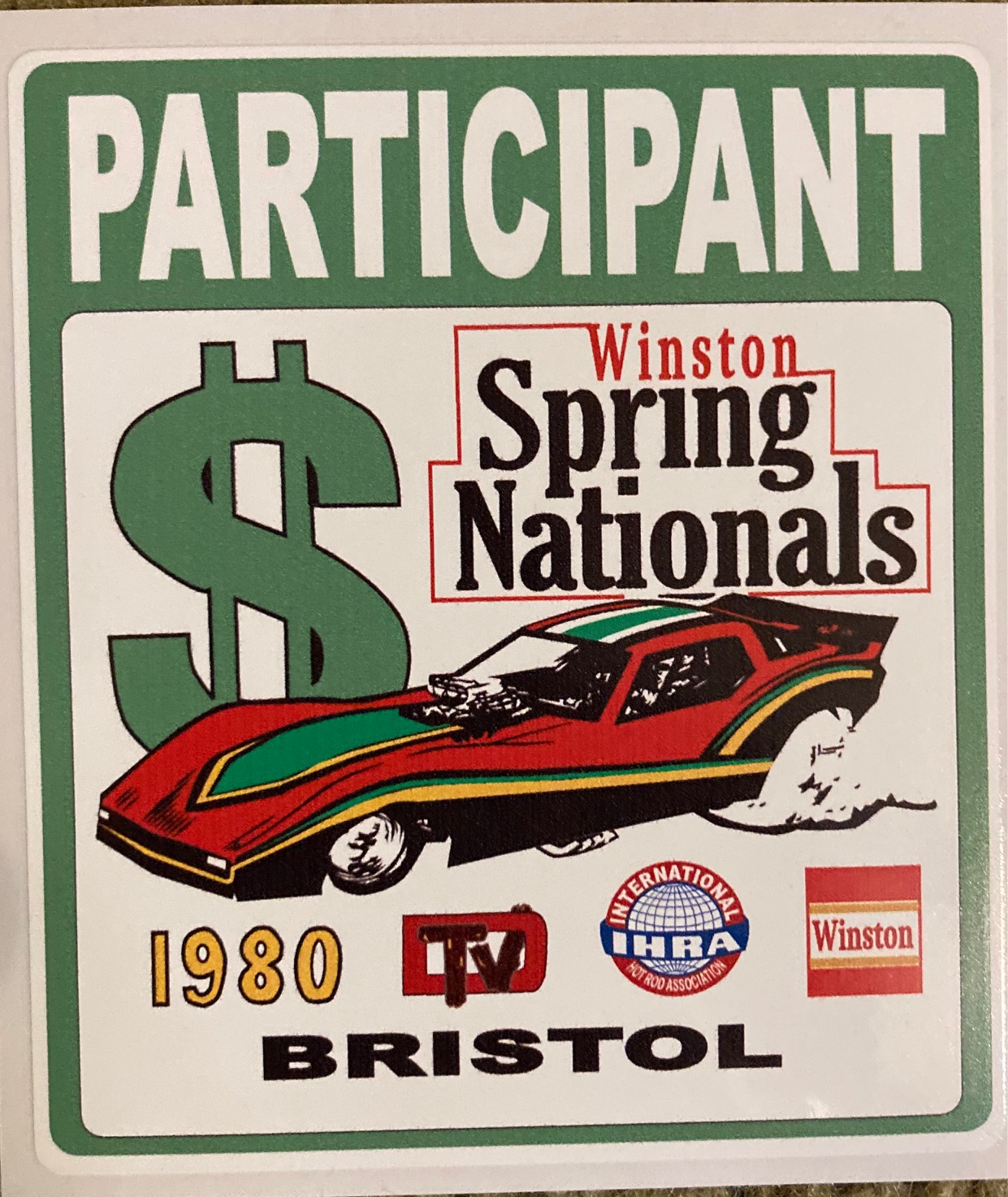

3. THE DASH FOR CASH BRISTOL IHRA SPRING NATIONALS

Larry Carrier was to Wally Parks what Foghorn Leghorn was to the Dog in the famous cartoons back in the day. If there was a chance to needle Parks, he did it.

Larry Carrier was to Wally Parks what Foghorn Leghorn was to the Dog in the famous cartoons back in the day. If there was a chance to needle Parks, he did it.

Opinions vary regarding the impetus of the big-money payouts at the IHRA Spring Nationals (two words since NHRA owned the rights to the one-word name). Carrier’s long-time vice president, Ted Jones, cited the series founder’s reluctance to continue paying appearance money for an event routinely rained out. Others said Carrier used the event as an equivalent to a kick in the groin to mock NHRA’s purse payouts.

Regardless of the inspiration, the IHRA’s payouts of $20,000 to the winning driver in Top Fuel and Funny Car and $10,000 represented a considerable step in compensating racers. This payout was the equivalent of $75,000 in today’s economy and, for the Pro Stockers, about $37,000. While not overwhelming by today’s big money standards, those big dollar paydays didn’t exist back then.

At the time, purses for the NHRA national events for the fuel classes were paying anywhere from $4000 to $5000 to win. The championship points earning divisional races offered in the range of $1200. And with the points chase set up where racers could waive points, there was a likelihood a racer could skip a race for a more lucrative match race.

But who could blame Carrier after the way the two parted ways?

“One of the last things Parks said to Carrier [as they parted ways in 1967] was Parks thought that the Bristol Tower was obnoxious,” noted drag racing historian Bret Kepner pointed out. “It was just too big and too overwhelming and too stupid. ‘That tower is going to be a monument to your failure.”

“And every Christmas, Carrier sent Wally a picture of the tower with this thing that said, “Merry Christmas, still standing.”

The one person who should have sent Carrier a Christmas card was Funny Car racer Billy Meyer.

The one person who should have sent Carrier a Christmas card was Funny Car racer Billy Meyer.

Meyer couldn’t seem to lose at the IHRA’s marquee event. He defeated the “other” Budweiser-sponsored Funny Car driven by Roy Harris in the 1980 event and scored final rounds in the next four IHRA Spring National big-money races, winning twice.

“That payday was a third of what I had in total sponsor money,” Meyer admitted. “For the first two years, when I made it to the final, I went and asked the other team if they wanted to split [the money], and they declined. I kind of always figured those winnings into my receivables list before the season started.”

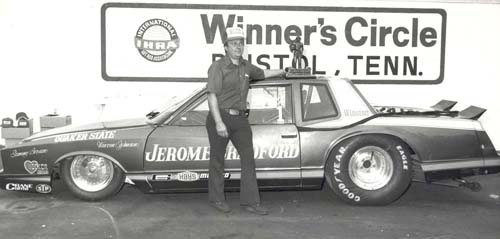

Warren Johnson, known mainly for his prowess in dominating NHRA Pro Stock, credits the IHRA for teaching him how to win. The Spring Nationals event kept him out of the poorhouse.

He learned survival skills following the 1979 event, which he won in the wee hours of a Monday morning in June. It was a victory he declared would be his last since he was $10,000 away from poverty, and announced his retirement only to return the next race and win the championship as well.

A funny thing happened on the way to retirement; Johnson met up with Buford, Georgia-based contractor Jerome Bradford.andd together they won the first two of the Bristol paydays.

In those days, the IHRA Pro Stock racers were often viewed as second-class racers, and even though Johnson began on the IHRA tour, he never let others’ opinions dictate the importance of what he and his fellow IHRA racers were doing on the largely regional series.

In those days, the IHRA Pro Stock racers were often viewed as second-class racers, and even though Johnson began on the IHRA tour, he never let others’ opinions dictate the importance of what he and his fellow IHRA racers were doing on the largely regional series.

“I never looked at it as any kind of an egotistical thing or comparison to one, the other,” Johnson said. “I raced for a living. I came from dire poverty, and I wasn’t going back. So I’m probably the only Pro Stock racer that, other than maybe Glidden, that actually made a profit racing because that’s the way I set my business up. If I lose money any year racing, I quit that year. It was strictly a business to me.

“So it was incumbent upon our team, myself, our team, to win those kind of races because that’s the stuff that paid the bills. Although Bradford didn’t care if I kept the money.”

In those days, $10,000 went a long way when it came to racing Pro Stock.

The Spring Nationals was such a big deal that in 1983, the Mizzlou-produced regional show actually became one of the first broadcasted events if you’re not counting the two Bud Lindeman Car & Track episodes.

The event remained a big deal until 1985, the last year Winston was involved in IHRA Championship Drag Racing. Each year after, the event lost a bit of its luster until it became just another race on tour, and eventually Thunder Valley, now Bristol Dragway, left IHRA for NHRA.

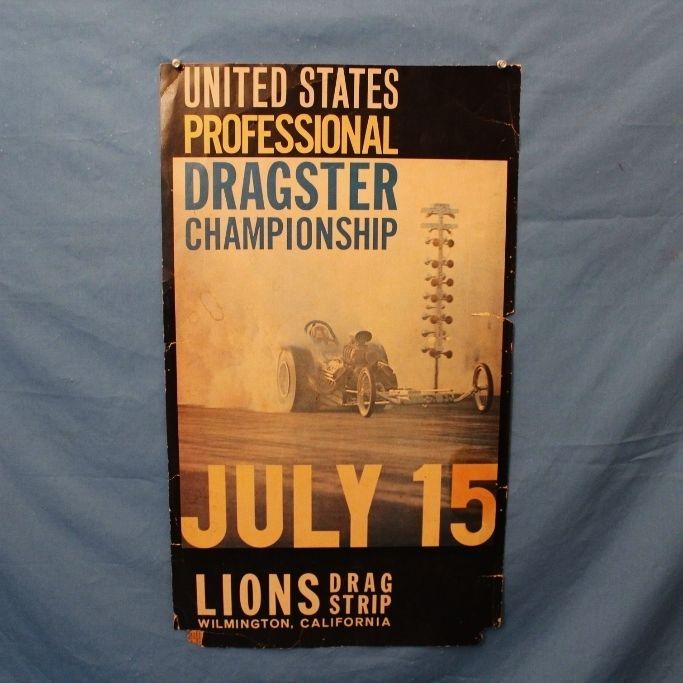

4. THE “ALL-DRAGSTER” PDA EVENT OF 1967

The moment you paid your $5 general admission (not including a $2 pit pass) and rolled through the gates at Lion’s Drag Strip, you immediately heard the theme from Mission Impossible start playing.

The moment you paid your $5 general admission (not including a $2 pit pass) and rolled through the gates at Lion’s Drag Strip, you immediately heard the theme from Mission Impossible start playing.

It was the first race for the newly-formed Professional Dragster Association [PDA] and its promoter, Doug Kruse, also an accomplished builder of dragster bodies.

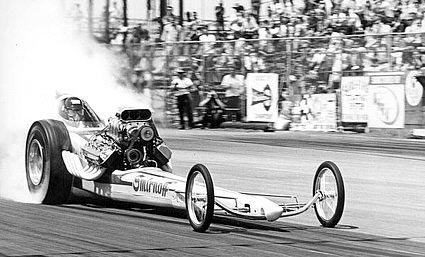

Essentially, 94 dragsters showed up for a one-day 64-car field race of Top Fuel dragsters. They qualified for the event, ran six rounds of competition, and finished at 4 AM.

“That was the most effective racer [event] I ever witnessed,” Hall of Fame drag racing journalist Dave Wallace confirmed. “The racers wanted bigger purses, so Kruse, who was a rabble-rouser, very smart guy, and educated, created the first PDA meet.”

The consensus was the dragster racers felt like they could put on a show, along with Top Gas and Jr. Fuel, and didn’t need the newfound darlings of the sport, Funny Cars, to fill the stands.

“They also had 32-car Top Gas and Junior Fuelers, so you can figure what a cluster that whole deal was,” Wallace added. “But it still delivered a great show.”

Logistically, how can a race with this many cars complete qualifying and six rounds of eliminations in one day?

Logistically, how can a race with this many cars complete qualifying and six rounds of eliminations in one day?

“Burnouts were not part of the equation,” Wallace added. “The burnouts really slowed the shows down. So in ’67, the dragsters weren’t doing burnouts. You could have two on the line, two pushing down and two waiting to run. You can have six cars fired at all times, sometimes eight. As soon as they staged and cleared the finish line, they’d clear the clocks, and the next cars would stage. The burnouts really messed up the show.

“That’s why San Fernando could have a three-hour show, a Top Fuel and Top Gas show, a Comp type show, they called Little Eliminator. You couldn’t do that in three hours, qualifying and eliminations with burnouts. That was the way we grew up. Everybody did in the fifties and sixties, the burnouts really, once the dragsters started doing burnouts, it took a while. It really slowed the show down.”

Additionally, according to noted drag racing historian Bret Kepner, there was only one two-hour qualifying session, where it was rare if a dragster got more than one qualifying run. In those days of drag racing, there weren’t set times and sessions for qualifying. A racer could get in as many runs as they wanted as long as they could get the maintenance done and come around for another run.

“It was a great race, but it did not stop the onslaught of the Funny Cars,” Kepner added.

“It was a great race, but it did not stop the onslaught of the Funny Cars,” Kepner added.

The dragster-only format lasted one year before Funny Cars were added to the show during the 1968 running. But by this time, drag racing had begun to evolve, and by 1969, burnouts had entered into the equation.

Eventually, Kruse sold out the PDA, which was quickly scooped up by promoter extraordinaire Bill Doner, who gave the events status at his various tracks up and down the West Coast. The PDA was essentially just a name with no real power behind it. In other words, it was just three letters.

As Wallace saw it, the most significant thing Doner brought to the PDA was pizazz.

“Doner brought a lot of promotion to it, a lot of pizazz, and brought it to Orange County Raceway, which was a much nicer facility than Lions,” Wallace said. “People don’t realize that Lions was a real basic facility. It was the greatest drag strip ever, but it was a very basic industrial kind of site where Orange County was really trick.”

As much pizazz as Doner brought, nothing he or the ever-changing drag racing world could do would ever bring back the magic of that first event.

5. THE ORIGINAL IHRA WORLD NATIONALS IN NORWALK

EMBED

6 – ANY OF THE SHUFFLETOWN DRAGWAY PRE-PRO MOD QUICK EIGHT EVENTS

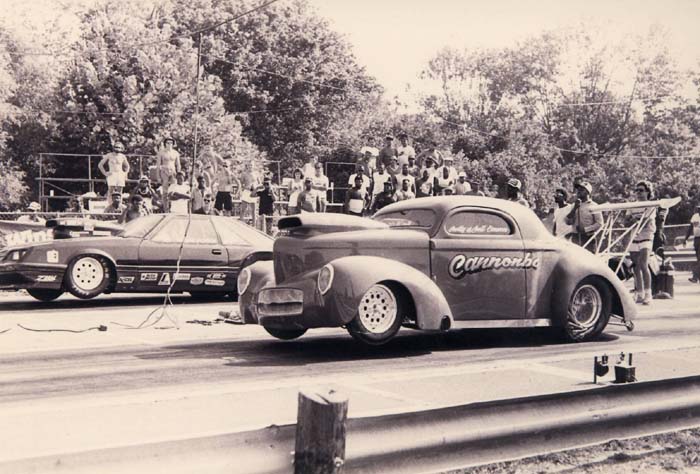

Shuffletown Dragway, the eighth-mile strip located outside of Charlotte, NC, was not the first place to run a Quick Eight event of what would have been the future Pro Modifieds. That honor belonged to Orangeburg Dragway in the lower part of South Carolina.

Shuffletown Dragway, the eighth-mile strip located outside of Charlotte, NC, was not the first place to run a Quick Eight event of what would have been the future Pro Modifieds. That honor belonged to Orangeburg Dragway in the lower part of South Carolina.

But just like Chick-fil-A, who didn’t invent the chicken sandwich but perfected it, Shuffletown didn’t create the format of running volatile doorslammers but they indeed perfected it.

Clinton Mashburn, the track’s promoter, had plenty of fast cars running at his track, now a dog park off of I-385. He had the cream of the crop for fast doorslammers, who had abandoned their Modified Eliminator roots for fast bracket racing in IHRA’s Top Sportsman. On any given Sunday afternoon, a drag racing fan could see future legends such as Charles Carpenter, Blake Wiggins, Michael Martin, Tommy Mauney, Walter Henry, and even Scotty Cannon racing Super Pro.

When venues such as the Orangeburg strip began to book them for match racing and later upped the ante to a well-funded Quick Eight, running these “bracket” cars heads-up, with no breakout, became Mashburn’s mission. Though these other venues often paid more, Shuffletown Dragway was a home track to many of these racers, and for them, there was no place like home.

“I remember those days,” said six-time champion Scotty Cannon. “We were just excited that we didn’t have to race with a dial-in on the car. There was no thinking that one day we were laying the foundation for a professional class. Honestly, we couldn’t have even thought that big. Honestly, we were more concerned with trying to make it to the finish line in one piece without running over someone.”

During the 1987 – 1989 years at Shuffletown, there were times when almost as much money changed hands trackside as on the New Stock Exchange. These events brought in the outlaw and the high-end Top Sportsman cars. Outlaws such as the Gaffney Brothers and their ultra-quick 1968 Nova, driven by Sonny Tindal and Thomas Jackson, piloting his ex-Rickie Smith Mustang Pro Stocker, were able to line up against Ed Hoover and Wiggins in these events.

“ We were excited because we had somewhere to race, but later our excitement just to race in a show like that faded away to show us the reality these tracks weren’t the safest ones to be racing on,” said Carpenter, who began racing at the track in a Modified car, the same one he’d bolt in a large-displacement engine with nitrous and run in the sevens.

We were excited because we had somewhere to race, but later our excitement just to race in a show like that faded away to show us the reality these tracks weren’t the safest ones to be racing on,” said Carpenter, who began racing at the track in a Modified car, the same one he’d bolt in a large-displacement engine with nitrous and run in the sevens.

“But yeah, it was definitely a big show back in those days. There was lots of money changing hands, and those who had the money didn’t mind showing you as you rolled up there to stage.”

Doug Mashburn was the youngest of Mashburn’s three sons and worked full-time at the track during this era.

“When Dad started running the Quick Eight events, he really had no clue what it would do to hold a place in drag racing history,” Mashburn said. “He just knew he had a bunch of fast cars in the pits. He wanted to race them against one another. It started out as a once-a-month thing, and then it went every other month and just blew up from there.

“Dad was tight on his money, and he just wanted to make a dollar. The entire track prep budget was six gallons of VHT that he bought from [announcer] Larry Wright. We’d spread it out to about 60 feet, and that was it. It was a once-a-day thing. Even then, he’d fuss a little about the cost of the VHT.

“It was really no-prep racing, but it turned into something big and special. We had no idea; it just happened. There’d be so many people there that you’d really have to search for somewhere to sit down to watch it all.”

Once Pro Modified became an official Pro Modified class, these events faded away, and in 1991, the track closed due to noise ordinances. The track had been in operation since 1957.

7. PRA NATIONAL CHALLENGE – TULSA, OK

On paper, it looked to be the greatest drag race of all time. The event promised to pay the most significant purses of all time, run by racers, and go head-to-head with the NHRA on its marquee race weekend. If only drag races were promoted solely on paper, the PRO National Challenge in Tulsa, OK, could have revolutionized drag racing.

On paper, it looked to be the greatest drag race of all time. The event promised to pay the most significant purses of all time, run by racers, and go head-to-head with the NHRA on its marquee race weekend. If only drag races were promoted solely on paper, the PRO National Challenge in Tulsa, OK, could have revolutionized drag racing.

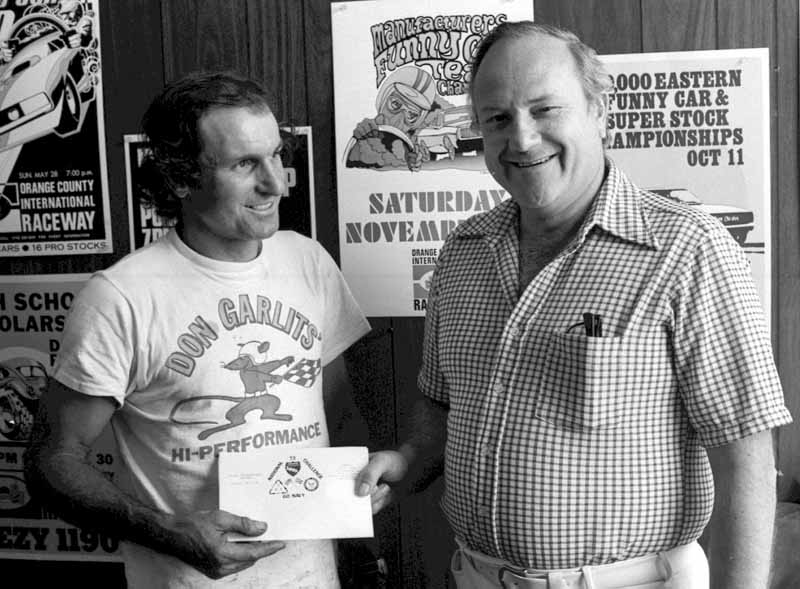

In 1971, with the Vietnam War raging, the United States motorsports community came together in a show of support for the troops during a USO tour at the request of Rear Admiral Emmet H. Tidd. The team featured the best of the best in all forms of racing and included the likes of Richard Petty, A.J. Foyt, Mario Andretti, and drag racing’s Don Garlits.

“The group of racers began talking about prize money,” drag racing historian Bret Kepner pointed out, “The others asked Garlits what was the most he ever won dragging racing and I remember the number specifically. Garlits told them his richest purse was $7,400 for his 1967 Top Fuel win at the NHRA U.S. Nationals at Indianapolis. That would’ve included contingency because I don’t think anybody was paying more than $3,000 to win Top Fuel eliminator before 1971.”

The other racers chuckled as Garlits told them his career-best prize winnings.

“When Garlits said $7,400, the others laughed at him,” Kepner continued. “They couldn’t believe their ears. They asked, ‘You’re racing professionally and only making $7,400?” Corrected for inflation, that figure equates to $65,453 in 2022 dollars. This embarrassing moment was all Garlits needed to inspire the Professional Racers Association and, inevitably, its marquee event, The National Challenge.

Four years later, Steve Carbone pocketed $6,100 ($44,301 in 2022 money) for winning the same event. It’s no wonder they laughed at the drag racer from Ocala, Fla., as Richard Petty’s 1971 Daytona 500 win scored $48,000, $356,454 in today’s currency.

Garlits used a group of investors, rumored to have included a handful of well-to-do drag racers, and a line of credit from a bank to pay a $25,000 winner’s purse in all three professional divisions.

In today’s economy, the winner’s purse equates to $177,219.50.

Because Garlits and the PRA wanted to make the most impactful statement, they put the event on Labor Day Weekend, opposite the NHRA’s U.S. Nationals, and did it at Tulsa International Raceway, one of the AHRA’s crown jewel facilities.

Sensing the NHRA could be competitive in the draw for professional drag racers, PRA returned to its backers with a phenomenal $35,000 winner’s purse ($246,925 in 2022), including contingencies, for the winner of each category. Even the runner-up money of $3,000, which, in the case of Pro Stock, was more than the NHRA winner.

The PRA also offered its first-round losers in each 32-car field an outrageous $500 ($120,111 total payout in 2022) ($3,527 in 2022).

The PRA also offered its first-round losers in each 32-car field an outrageous $500 ($120,111 total payout in 2022) ($3,527 in 2022).

With ego firmly in place and fiscal responsibility out the window, the PRA National Challenge purse ballooned to $151,000, the equivalent of today’s

$1,065,308. The increase in purse meant the promoters would have to sell 96,000 tickets at $11 apiece. In today’s economics, the ticket would have fetched $77.61.

Even in drag racing’s so-called glory days, the event had a losing proposition written all over it before the first tire had turned under power in the burnout box. The Tulsa track seated just over 8,000 spectators. A last-minute bid by Tice made the facility better but far short of what it needed.

While the 1972 PRA National Challenge has largely been recognized as drag racing’s most prominent professional-only show, unbeknownst to many, the event held sportsman drag racing starting on Tuesday and finishing on Thursday.

Additionally, the PRA declined to charge any professional team an entry fee, thus neglecting another revenue stream to supplement what was to be a weak income-to-expense ratio.

At the last minute, the NHRA, fearing low car counts for its marquee event, adjusted its schedule to enable teams to compete at both events.

NHRA President Wally Parks issued a statement shortly after the schedule adjustment.

“Most of these drivers have two cars, and if they have that much determination, we feel they should get a chance to qualify on Wednesday so they can run at Tulsa,” Parks said.

“Several drivers said, ‘We can’t pick one race or the other; our sponsors won’t allow it,” Kepner explained. “So, a few teams raced at both events. This was possible because the Tulsa race started on Friday and finished on Sunday. The NHRA began qualifying at Indy on Wednesday and ran eliminations for all classes on Monday. Remember, this was almost ten years before established qualifying sessions so the teams could make as many runs as they could get on Wednesday and Thursday at Indy.”

Tulsa was going to be the winner in the car count battle and was drawing roughly 200 professional teams, a number that overshadowed the NHRA’s best car count. Still, it drew an additional 500 or so sportsman entries, far less than Indy.

Multiple teams made the 750-mile one-way trip from Indianapolis to Tulsa after qualifying on Wednesday and Thursday. Then, those teams which managed to stay qualified in the NHRA U.S. Nationals field pulled out of the pits after Tulsa’s Sunday eliminations as soon as they lost to make the blazing 750-mile straight-through return trip to Indy after for a possible five rounds of competition on Monday.

Ultimately, the event in Tulsa reported ticket sales of 37,522, far below the 96,000 threshold. Don Moody (Top Fuel), Tom McEwen (Funny Car), and Bill Jenkins (Pro Stock) took home the winning titles.

Hall of Fame photographer Steve Reyes said there were bad omens from the start at the opening event in Tulsa.

“The first funny car down the track and this will tell you how the whole event in ’72 started,” Reyes explained. “First Funny Car down the track was Jake Johnston in Gene Snow’s blue car, the blue Charger, huge fire. First funny car to make a pass at that event. There’s probably three people in the grandstands, and [Johnston] comes down there and just woofs one.”

The event added to Reyes’s collection of iconic drag racing mayhem shots, including a pair involving Top Fuel racers Bob Dumont and Larry Brown.

“Pure mayhem,” Reyes added. “When you have dragsters throwing the engines out of the car, that’s pretty spectacular. It was all a warm-up for the Jeb Allen – John Weibe crash of 1973.”

While there were no financial winners outside the racers who won, the series scored a few personal victories.

Tice, who had secured the rights to sanction the events for the first five races, was able to throw dirt in the face of his sanctioning body rival Wally Parks.

Because of his relationship with Admiral Tidd, Garlits was able to procure marketing support from the United States Navy for the event and series, and later a personal sponsorship. It’s hard to say whether the event was a failure or merely broke even, as there were conflicting statements.

However, Garlits, President of PRA, said the event only caused a lifelong rift between him and Parks.

“Wally and I never spoke of the event, ever,” Garlits told Bangshift.com’s Brian Lohnes. “He never to his dying day forgave me for challenging “His” Nationals.”

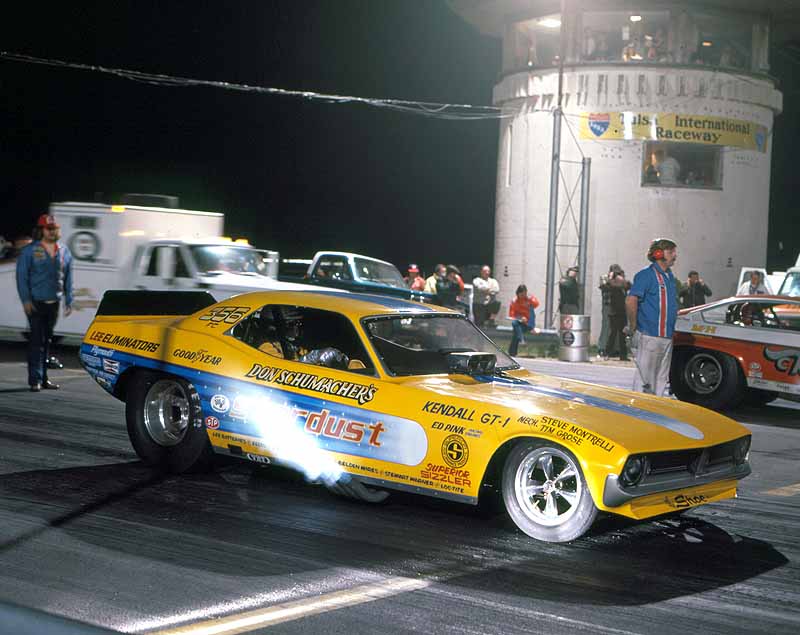

8. ORANGE COUNTY’S FUNNY CAR MANUFACTURER’S MEET

The Orange County International Raceway Funny Car Manufacturer’s meet lived up to its name in every fashion when unveiled to the drag racing world over the Thanksgiving holiday week of 1967.

The Orange County International Raceway Funny Car Manufacturer’s meet lived up to its name in every fashion when unveiled to the drag racing world over the Thanksgiving holiday week of 1967.

The biggest gripe amongst drag racing fans is that the Funny Car bodies are largely unrecognizable when compared to the cars they are to resemble, and all of them have an engine based on the Chrysler Hemi. On this first event, and for a few afterward, the carpet matched the drapes for those Funny Cars.

Most of the Chevrolet Funny Cars had Chevrolet engines, the Fords had Fords, and the Chrylers had Chryslers. And, according to noted drag racing history Bret Kepner, the first event was a hit.

“Sold the place out,” Kepner added.

On an 18-inch seat, it was estimated OCIR could hold as many as 12,000 spectators, with a sellout likely capping out at 10,000. The first race paid a reported $22,000 purse, and one of the treats was a team format where the racers gained points for their respective manufacturers.

The format featured six teams with five cars per team; they each earned points for their team. There were 30 cars with a reported 15 alternates on the property. Every time a car won, they scored a point for their brand unless they were an alternate, and this paid out a half-point per victory. Today, it would be considered a Chicago-style format with three rounds, and the two quickest winners met for the overall title.

“That was a bought in race and there were six teams of five cars each, and they were broken down by manufacturer,” Dave Wallace, a Hall of Fame journalist, added. “What people don’t realize is, in 1967, at the first manufactures Meet, right after the track opened, the Pontiacs were still powered by Pontiacs and the Plymouths were Chrysler stuff. The Chevrolets were still powered by Chevrolets.

“You had Plymouth, Dodge, Chevrolet, Pontiac, Ford, and others. Almost all of them were still powered by the make. That was expected in the first year as the Funny Cars. You didn’t have Chryslers in Mustangs, that kind of stuff. A few people put a 392 into a Mustang body or something. But basically, the reason that race was so popular is because you could cheer for your brand. When they lifted the body on a Firebird, it was a Pontiac engine, not a Chrysler.”

The first team championship, through our research, was claimed by Chevrolet. The members of the team were Doug Thorley, Terry Hedrick, Dick Harrell, Kelly Chadwick and Ron O’Donnell.

The first team championship, through our research, was claimed by Chevrolet. The members of the team were Doug Thorley, Terry Hedrick, Dick Harrell, Kelly Chadwick and Ron O’Donnell.

“When you look at the first year, they were mostly Southern California cars that were booked in,” Wallace explained. “A few exceptions, but you didn’t have Prudhomme, McEwen, and all those guys. Nobody knew that thing was going to become such a huge deal. That put Orange County on the map. Nothing before that really was big like this.”

OCIR opened its gates as drag racing’s first real, purpose-built super track. Then, the event in November ignited like a wildfire.

“Nobody knew it was going to be such a huge thing until after the first one,” Wallace said. “They put all the cars on the track; they didn’t fire. There’s people just bringing them out on the track like that. I don’t think it’d ever been done before. There were parades before eliminations in past years, but they did not bring all the cars out, put them on the deal, let the band play, and all that stuff. That was real showmanship.”

Eventually, the changing face of fuel racing made the event one in name and body style only. It lasted until the track shut down in 1983, but for the first few years was one of the most profitable events the track hosted.

“It was like having the world’s biggest match race,” Wallace added.

“You had one winner, but the team concept was the original deal. Which team is going to win? And again, back then, you could cheer for your engine. They were real cars. Well, not real cars, but you know what I mean. The engine was consistent with the body, which was important.”

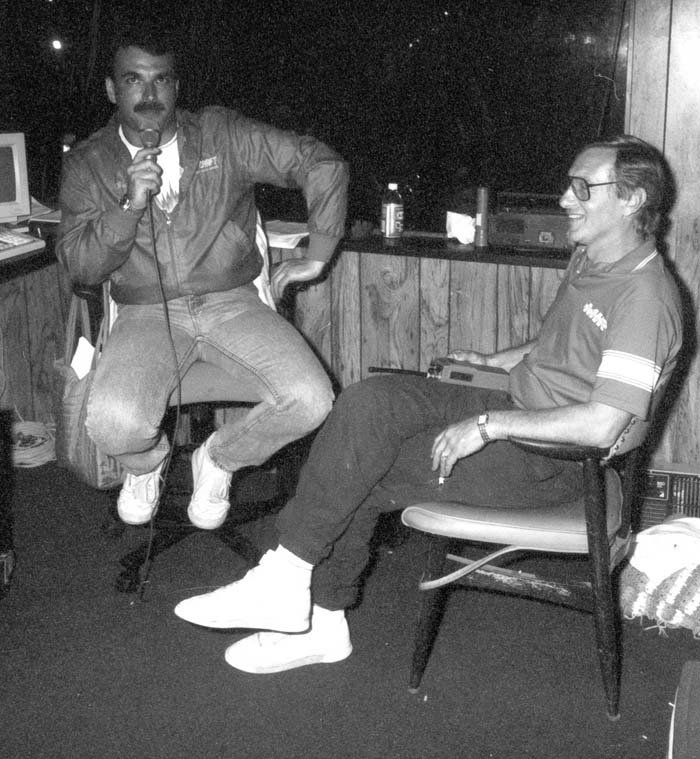

9. THE ORIGINAL UNITED STATES SUPER CIRCUIT

The vision of promoter Duane Nichols only served notice that Pro Modified was coming before the name ever existed. If he proved one thing on the original weekend of the United States Super Circuit, these sportsman racers, then Top Sportsman racers, were ready to take on the world of professional drag racing.

The vision of promoter Duane Nichols only served notice that Pro Modified was coming before the name ever existed. If he proved one thing on the original weekend of the United States Super Circuit, these sportsman racers, then Top Sportsman racers, were ready to take on the world of professional drag racing.

Top Sportsman was an IHRA thing back then, and because the IHRA ran primarily east of the Mississippi, the chances of getting to see these cars splashed all over the magazines were slim to none.

“There was demand from both track operators and fans for that kind of thing at that time period of our history in drag racing,” said Nichols in a 2010 CompetitionPlus.com interview. “The Pro Mod thing was so hot for a time period there that everybody was screaming for it.”

Nichols’ USSC [United States Super Circuit] debuted in 1989, inspired by one of his previous promotions featuring Pro Stockers of the late 1960s.

“When you are a kid, and you watched the different trends in drag racing and how people flocked to watch them and paid to do so, we realized that we had made that grade,” said Bill Kuhlmann of the USSC experience. “We were finally at the point, where the people are who were our idols when we were young.”

“When you are a kid, and you watched the different trends in drag racing and how people flocked to watch them and paid to do so, we realized that we had made that grade,” said Bill Kuhlmann of the USSC experience. “We were finally at the point, where the people are who were our idols when we were young.”

Nichols understood the USSC enabled these “professional” sportsmen to conduct themselves as true professionals.

“If you talk to some of those original guys, I’m sure they’ll tell you the same thing I am telling you – there was something magic about it,” Nichols said. “They got a taste of what professional racing is really all about.”

On those two nights, the finest of the finest in fast doorslammer racing battled it out before packed grandstands and race fans, many of whom couldn’t get enough of these on the edge of out of control cars.

The Budds Creek race was won by Rob Vandergriff who beat “Animal” Jim Feurer in the final round of the Chicago Style events. The next day, newcomer Mike Ashley not only beat Vandergriff in the final round, but also established the fastest doorslammer speed ever at 211.26 miles per hour; nearly five miles per hour faster than anyone had ever run in this style of racing.

Amazingly, Nichols had told Ashley earlier in the week he couldn’t run the series because he already had enough cars.

“Yeah, I told him that I would just enter the bracket portion of the events and embarrass all of his cars,” said Ashley, who didn’t have a reputation in the class yet.

Ashley was given a place in the show due to breakage among the regulars.

“I will never forget the first time he showed up,” recalled Nichols. “He pulled in there with his whole family. They had this unbelievable truck and trailer. They set up tables and put the tablecloths down; brought out the beers and champagne. His parents and family arrived in fur coats dressed to the tilt. That put him on the map overnight, that event.”

Combining the magic of all the USSC players with the new kid’s outlandish performances did well for the tour’s reputation.

“I think this was part of the magic,” Nichols said. “The fans could really see that this deal was for real. These guys were on kill. They were there to win. You could see it. You didn’t have to be involved. You could be a casual spectator and feel it in the air – that these guys were there to win.”

Nichols was quick to point out the USSC was so much more for the race fans than just a Pro Modified equivalent to the early Coca-Cola Cavalcade of Funny Cars in the 1970s.

“I don’t think the Coca-Cola Cavalcade ever quite had that magic,” Nichols said. “The draw on the Cavalcade of Stars was placing as much as anything to the track operators. It was a way of getting Funny Cars in an organized manner. From a track operator’s standpoint they were able to get the best cars in the business in an organized form with a guarantee they’d really be there.

“The difference is, the feeling that the fans had towards these cars, it was like a rock concert. These drivers were like rock stars to them.”

|

![]()