Like moths to a literal flame.

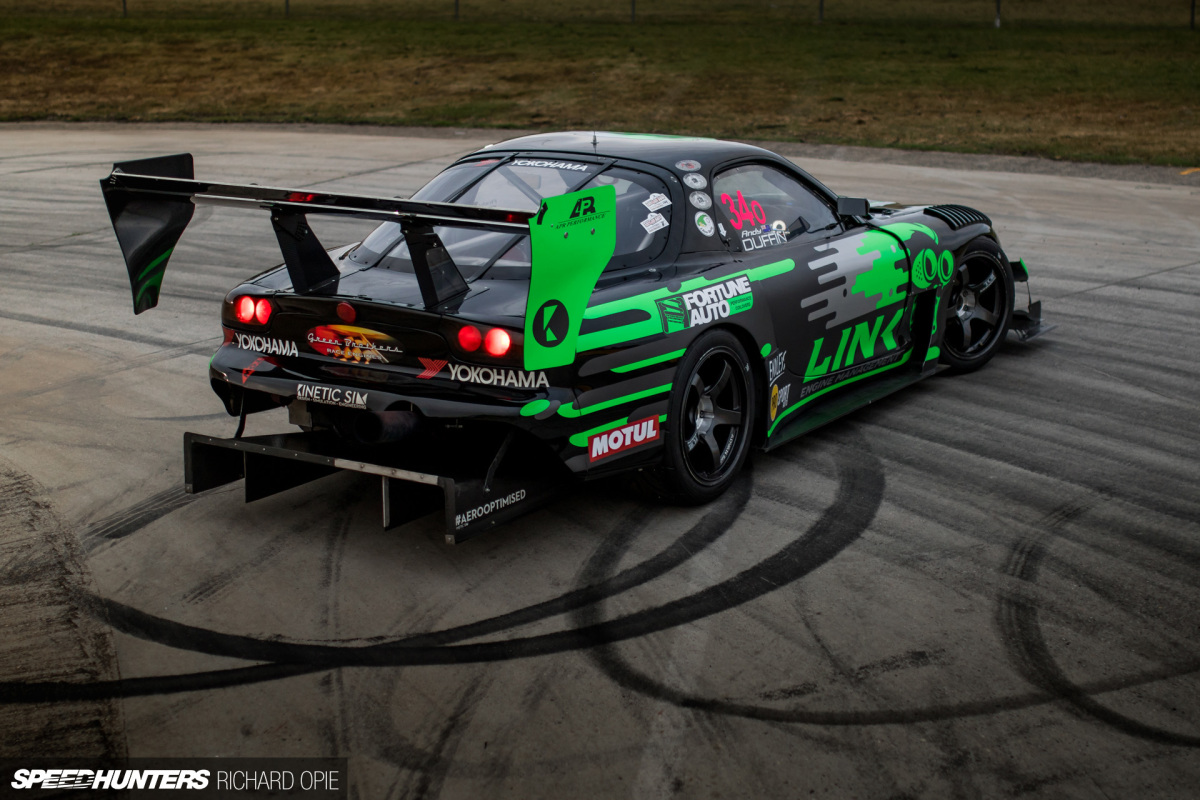

There’s no more concise way to describe the visceral attraction to Andy Duffin’s time attack focused FD3S Mazda RX-7. The moths, of course, are the Yokohama World Time Attack Challenge faithful. The flame? Even a casual glance in the direction of Andy’s weapon as he buttons off, deep into the braking zone, can explain that one.

The RX-7 is the perennial showman of the annual track addiction festival in Sydney, Australia. It’s a tough crowd to stand out amongst, but Andy’s RX-7 has the fundamental elements down to a fine art, traits that can be attributed to a background in the Kiwi rotary scene.

That’s right, Andy and the RX-7 are born and bred in New Zealand, home to some of the finest architects of rotary culture. Since the early days, Andy’s been immersed in a lifestyle of powerplants that go round and round, not up and down.

It’s a facet of Kiwi car culture that’s arguably built on disrupting the peace. The alto-pitch singing of spinning rotors has long been an institution on local tracks and streets, overpowering the lumpiest bent-eight and the whistliest DOHC turbo.

It’s almost natural then, that Andy’s RX-7 is one of the enduring crowd favourites of WTAC. It continues soliciting staunch nods of approval as it screams down Sydney Motorsport Park’s front straight at the top of 6th gear, even after three straight years of attendance. It’s the rotary mantra; they simply grab attention.

Hooked at 16 years of age, Andy embraced the rotary life with full force. “I’ve pretty much owned them all; I think the only one I haven’t is an R100,” he explains of his affection for all things Mazda rotary. “There’s a few I regret selling, definitely.”

While screaming around the streets, undoubtedly baking the odd set of fat 13-inch tyres, sufficed for a while, the genesis for Andy’s switch to a circuit focus was a Series 1 RX-7.

“We put a cage in it, and thought we’d have a go. That’s really where it all started.” Competing initially amongst a bunch of much faster cars, the well-trodden path of racers prior soon attracted Andy. In a quest for victory the builds became a bit more serious, and although Andy achieved some success he admits maybe he didn’t give it the best possible shot.

Andy even built up a naturally aspirated, peripheral port 12A-engined Series 6 RX-7, which was one of the first FD3Ss running among the SS2000 class ranks. Responsibilities and family life meant the racing soon took a break, but the sense of unfinished business never quite vanished.

The flame was further fanned by seat time in friends’ rotary racers and a Pro 7 series title won behind the wheel of a borrowed Series 1. Following that win, Andy finally got back into the game with an FD of his own, again taking out a couple of New Zealand titles in the restrictive Pro 7 Plus class before deciding the FD was going to get “the treatment.”

Andy returned to the SS2000 ranks around 2004, with the build ultimately destined to morph into the time attack weapon of today. Starting with a tidy street car, the build originally packed a fuel injected 13B, before the weight advantages available by virtue of running a smaller 12A led to a 290whp peripheral ported variant of the smaller lump.

Revving to 10,000rpm and running right to the weight limit, Andy reckons the car was absolute bliss to chuck through the corners. But the 3-rotor howl was beckoning at this point; things were about to get properly serious.

It’s Business Time

Even the guys with the raddest cars get inspired, and Andy’s inspiration came from a guy called Mark Porter. The uppermost “run what ya brung” style race class in New Zealand is a series called GTRNZ, and during the 1990s Porter campaigned what is still to this day one of the wildest circuit rotaries to be raced in the country.

20B. Flame-spitting. Wide body. Fat tyres. Aural indulgence. That’s the Porter RX-7 in a nutshell, and it set Andy on a course for a 20B of his own. Of course, a step up to run with the big kids was going to be in order, but having won the SS2000 championship with the 12A, the time was ripe for evolution.

The resulting engine package still powers the car today, albeit in a fine-tuned state thanks to a few years’ worth of development. With the Green Brothers handling the mechanical side of the equation, sitting low beneath the carbon hood of the FD is a dry-sumped, naturally aspirated 20B.

It’s not really a case of reinventing the wheel, though. Inside the motor, Series 5 13B rotor housings wrap around a blueprinted, lightened and balanced rotating assembly. Naturally, peripheral porting is the chosen method of getting the 20B to breathe freely.

Internally, the engine is assembled with genuine Mazda parts throughout, an attribute credited with endowing the 20B with impressive reliability. Also ensuring reliability are Ianetti Ceramics apex seals. The ceramic seals are much harder than carbon variants, meaning increased lifespan and detonation resistance.

Induction wise, beneath the sealed carbon airbox the 20B is fed by a trio of throttle bodies. The whole lot is controlled by Link’s most advanced ECU option, the G4+ Thunder.

Witnessing the FD screaming down the front straight of SMSP bearing the branding of a Kiwi-made product, spitting flames produced by a Kiwi-built and developed 20B, is enough to make even the staunchest New Zealander shed a tear in the name of patriotism.

While it can’t be run on Kiwi circuits, WTAC permits the use of nitrous oxide. Being naturally aspirated in a predominantly turbo Open Class field, Andy and the team needed an equaliser and nitrous was the answer. Unlike Vin Diesel’s FD, the delivery isn’t simply a solenoid that’s open or closed; nitrous is moderated by an ECU-controlled stepper motor. This increases or decreases flow measured through RPM, gear and throttle position parameters, maintaining a predictable and tractable power delivery.

The total sum of the combo? Around 515hp at the treads, with the nitrous system adding around 150hp when maximum flow is achieved. Coupled to a rev limit of 10,500rpm, it’s little wonder the F1-esque howl of the 20B endears itself to the crowds, courtesy of absolutely no mufflers.

Even the gearbox keeps it Kiwi. Andy’s elected to use a TTI GTO 6-speed sequential, coupled to a Quarter Master twin-plate clutch. Interestingly, the diff is still a stock FD unit, albeit fitted with a Mazdaspeed LSD center.

Beneath the bodywork, things are fairly conventional. Fortune Auto Dreadnought coilovers take on the bump and rebound duties with individual adjustability, while chromoly adjustable swaybars and a swag of Hardrace adjustable bits and pieces enable fine tuning of the chassis.

The super-soft variant of the WTAC control Yokohama Advan A050 tyres measure 295/35R18 and fit over Advan Racing TCIII forged wheels. Beyond is a full Endless brake package, with 4-pot front monoblock calipers and 2-pot rears clutching floating brake rotors.

Aero Necessities

It was at the Leadfoot Festival a few years ago when Andy first met WTAC organiser Ian Baker, subsequently receiving an invitation to run in Australia and bring the 20B scream and lingering flames to the event.

“I thought, we were quick here, so we should be sweet over in Sydney,” Andy surmises. In fact, until the meeting with Baker, Andy admits he didn’t really know what time attack racing was.

Up until this point, the aerodynamic considerations had been minimal with the FD running little more than a basic wing and front bar combo. The need for an improved package to keep up with the established Open Class teams quickly became a priority.

At this stage, Auckland aerodynamic engineer David Higgins of Kinetic Simulation stepped in to assist with the development of a rule-compliant aerodynamic package. WTAC’s Open Class permits restricted development, so three key areas were identified in order to improve downforce without creating too much drag. Without the ability to simply crank up the boost and overcome ‘air brake’ style aero, the brief called for a slippery, efficient aero solution.

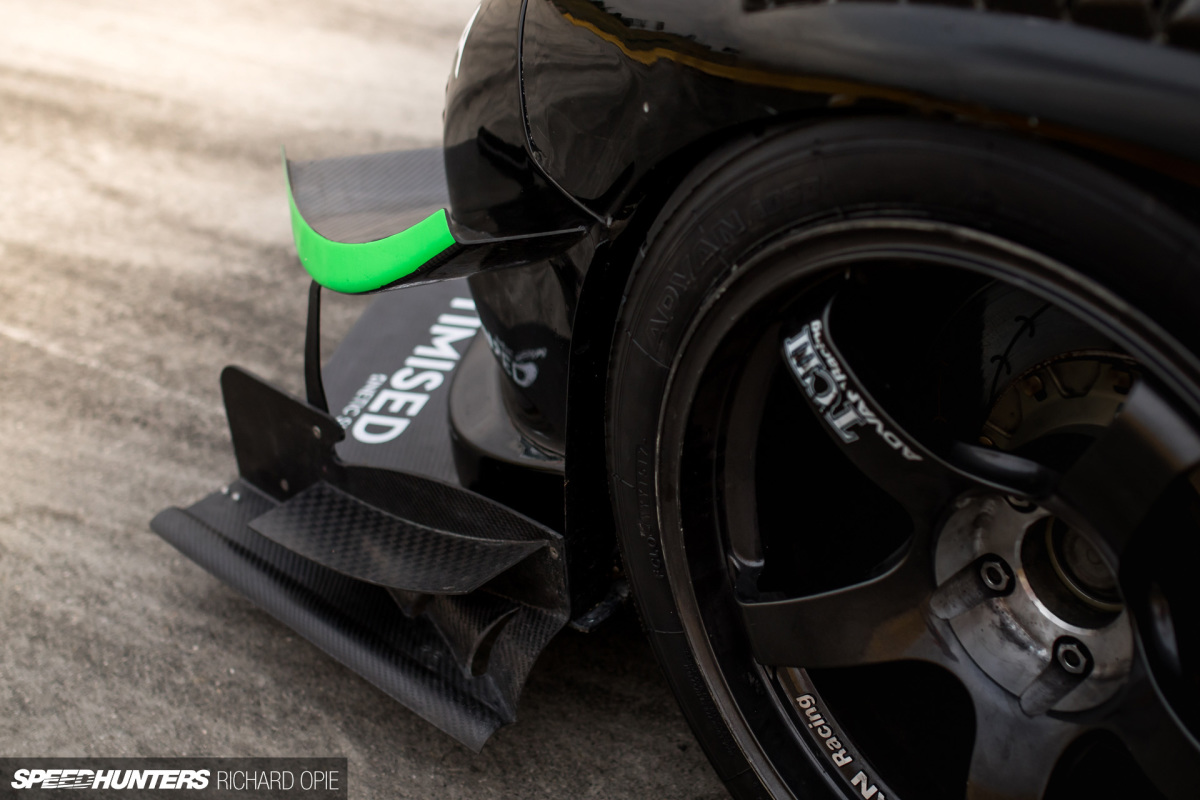

At the pointy end, the front splitter and under-tray combination provide the most crucial driving factor of aero performance. The under-tray diffuser shape is classified, but the end plates capping each extremity of the splitter are designed to maximise diffuser efficiency by keeping airflow attached at the splitter’s outboard ends.

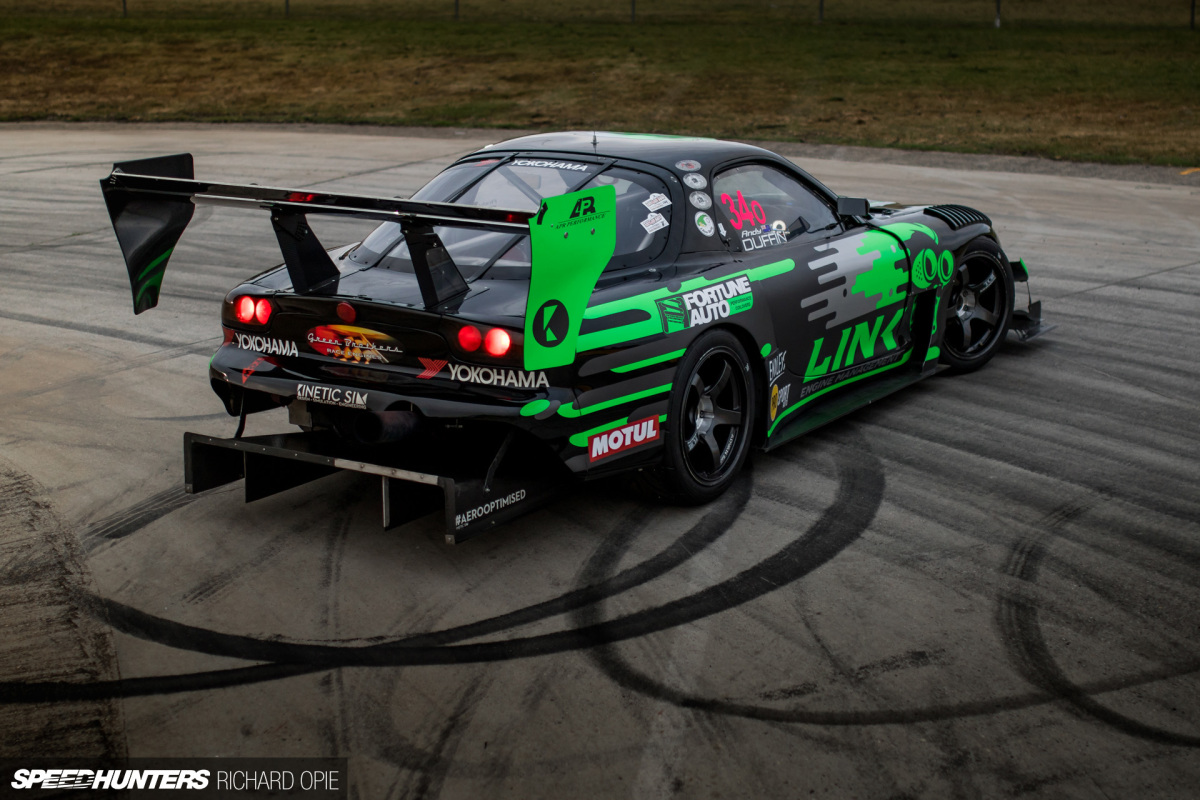

Fender louvres and sealed heat exchanger ducting through the nose and bonnet further reduce lift in the front. Along the flanks, rule-bending side skirts actually extend inwards beneath the car as much as allowed to mimic the advantages offered by a flat floor. Out the back, the requisite big wing, in this case an off-the-shelf APR dual-plane item with bespoke 3D end plates aimed at matching the flow coming off the rear of the car.

As per any self-respecting time attack car, the whole package is manufactured in carbon and fibreglass with moulds by Sandbrooks Rennenglass and manufactured by local composite-whisperer Tim Dorset.

Andy casts no illusions about the car being a one-man show built in a rickety shed. The sentiment is the opposite; the creation and campaign is very much a team effort, with the Green Brothers and Higgins accompanying Andy on the WTAC campaign. Everyone mucks in to help keep the show improving.

Andy and the FD first made it to WTAC in 2015, having never visited the Sydney circuit. With limited testing and no nitrous, Andy brought the RX-7 home 7th, with a 1:32.81 lap time. For 2016 the times improved, although the nitrous wasn’t working as planned in its first year. Still, it was good enough for 5th and over 2 seconds faster, with a 1:30.48, solidifying the RX-7’s intent as an Open Class challenger.

2017’s third outing, by rights, should have been even more successful. The engine was stronger than it had ever been by virtue of extensive dyno tuning to get the 20B and N2O hit working in harmony. The FD was glued to the track with even more tenacity thanks to minor aero tweaks. To Andy and the team’s frustration, a chassis setup issue curtailed chances of a top five result. A 1:31.17 lap was as good as it got, with Andy pulling no punches describing just how tough it was trying to solve their issues and drive through them.

Nevertheless, the crowd still welcomed the screaming, fire-belching RX-7 with open arms, which leads to the question, will it be back at WTAC? Andy’s keen, although he reckons they’ll need to sit down and crack into thinking about how to go faster. The obvious answer is turbocharging, but Andy vehemently denies this particular chassis will end up with boost. What it does mean, is the front straight of SMSP may reverberate again to the sound of Kiwi rotary royalty.

Richard Opie

[email protected]

Instagram: snoozinrichy

Cutting Room Floor